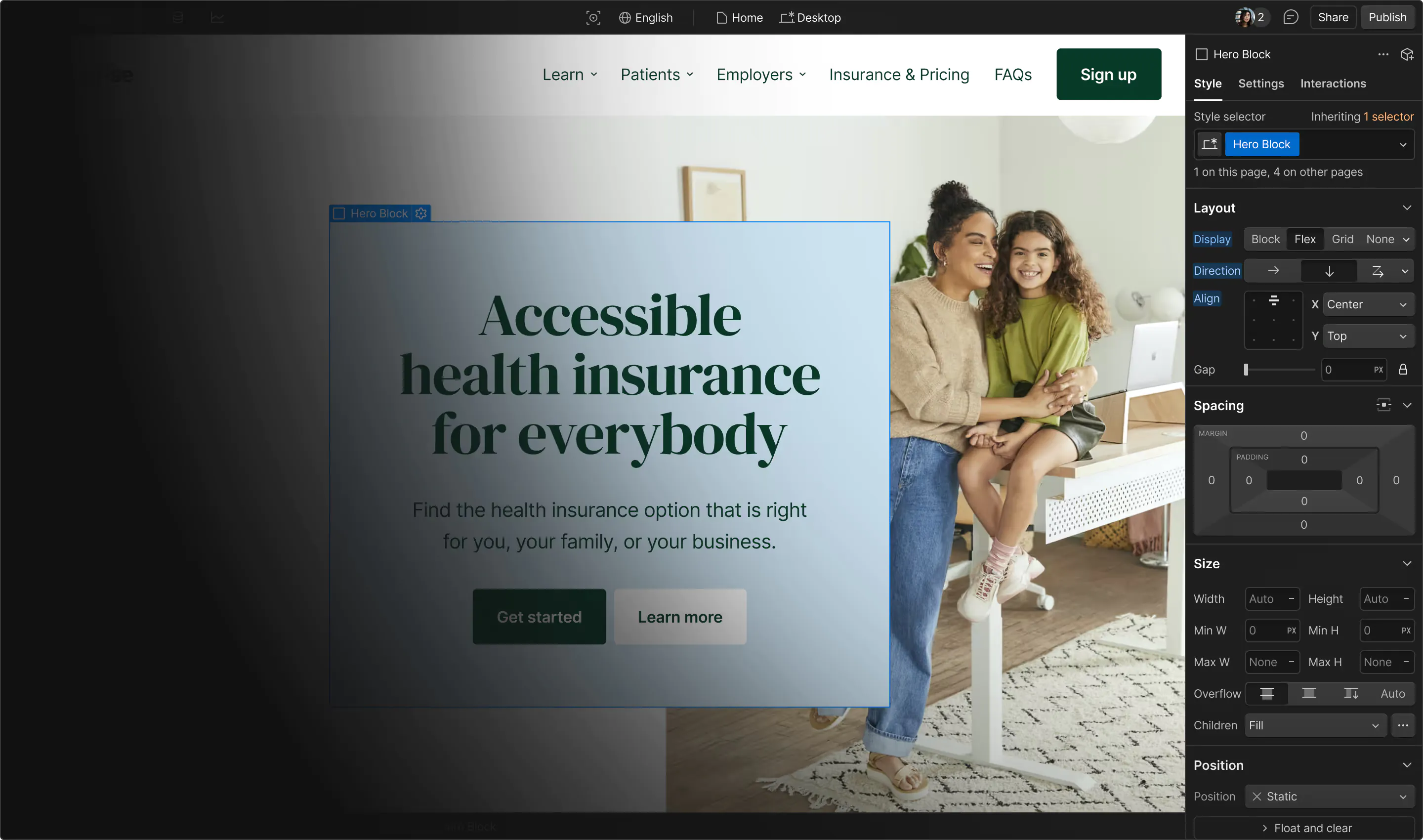

You've met with your client and defined your project’s goals. You understand the scope and have worked with the client to define a clear goal. You breathe a sigh of relief, knowing everything is in place for you to get started. But then things start to change …

Suddenly, the client has a better idea of what you can do to make the project a success, which, yes, will involve some additional work you didn’t talk about earlier. You've worked hard, but the client now wants to change direction, making everything you’ve done a waste. What you thought was a straight shot to launch has turned into a meandering journey through the backroads of indecision.

Welcome to the wonderful world of scope creep.

What is scope creep?

You’ve probably heard the term somewhere. But what is it? Is it some sort of curse? If you say “scope creep” three times in front of your laptop, will the simple website design you’re working on turn into an an email campaign, social media contest, and a logo redesign?

Thankfully, no.

When a project grows beyond what was agreed upon in the beginning, you've got scope creep on your hands. It’s okay for a project to evolve, but if it puts you in the position where you’re doing more work for the same money, then it’s a problem.

Here’s a few ways to handle it—before it turns this project into a living nightmare.

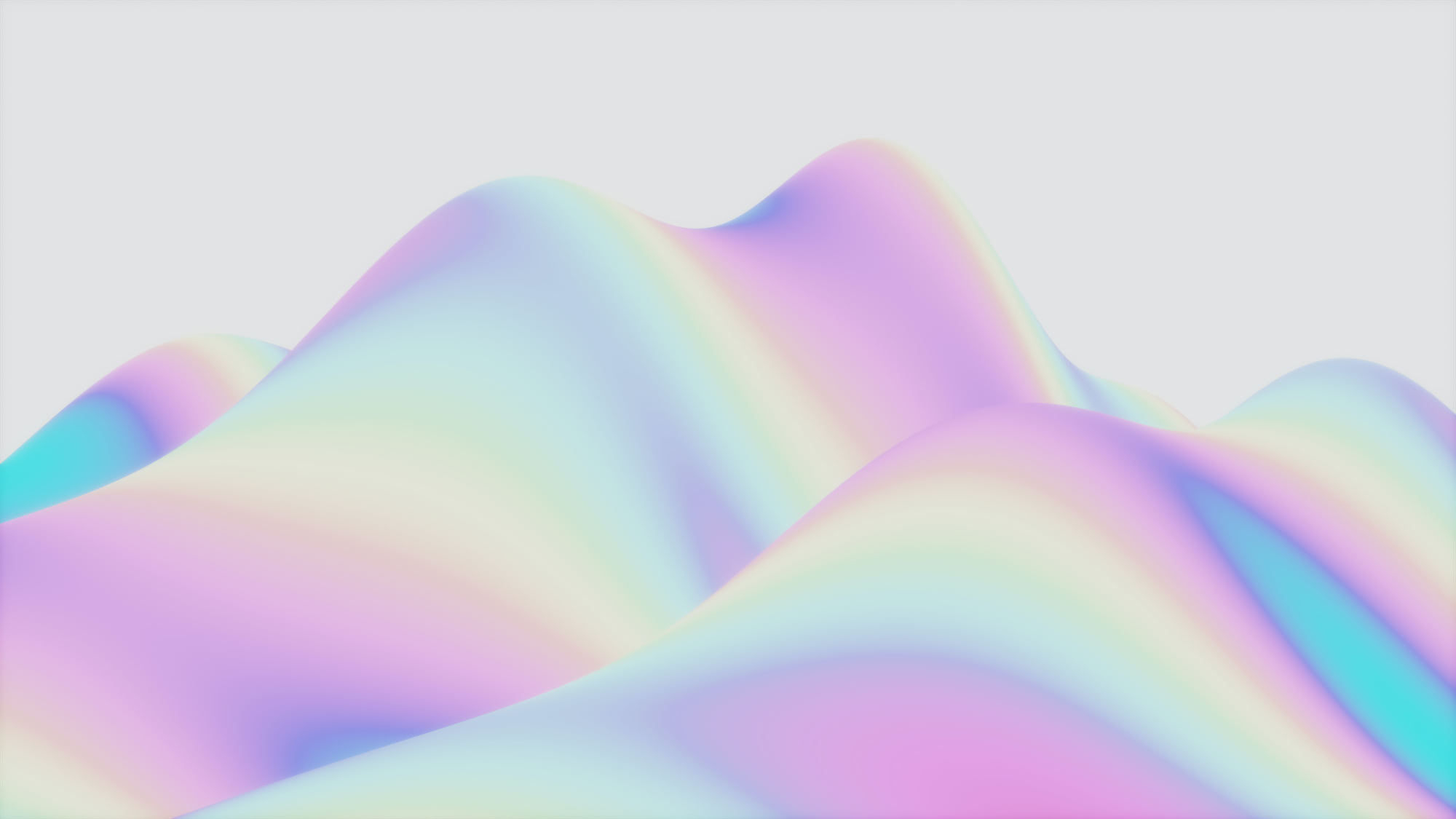

Define project scope in your contract

We know — you’re a freelancer. You enjoy the freedom of living every day as if it’s casual Friday. You’re working outside the lines of the traditional 9 to 5. You like to keep things “chill.”

Unfortunately, being too informal can mean setting yourself up for disappointed, frustrated clients. Which is so very unchill.

After a couple meetings with a client and other stakeholders, you should have a very clear idea of the project and its objectives. This is the moment to put all of the important details you’ve discussed about the project in writing.

Detail the work you’ll do — and what you won’t

Define what services you’ll be providing. Be direct and detailed in your language and make it clear how you’ll bill your client, whether it’s an hourly fee or a set price for the entire project.

For example, you could define scope like this:

I’ll build and launch five web pages, including:

- Home

- About

- Services

- Contact

- Blog

Content for these pages will be provided by the client by XX/XX/XXXX. If content isn’t provided by that date, the project timeline will need to be extended.

Each page is subject to up to 3 design revisions. Additional revisions will be charged at a rate of $X.

You’ll also need to detail types of work that will fall outside the contract, like excessive revisions, and how you’ll bill the client for these “extra” services.

To continue the above example, you could add the following:

Any pages added to the list above will add 1 week to the project timeline. Content can be produced for any of the above pages, or any additional pages, at a rate of $500 per page.

Ask for portfolio usage rights

If you want, you should also ask if you can use examples of the work you’ve done for your own portfolio, and if they agree, note this in the contract. It’s important to be flexible on this point, assuming you want the project, as some clients might be okay with you using work samples as long as their company name is omitted, or as long as the portfolio page is password protected.

It’s a bummer to create something great for a client, only to discover later that you can’t use it for your portfolio. I’ve been there dear reader, and wish that I’d asked about this ahead of time. But, lesson learned.

Include a kill fee or down payment

Sometimes a client will decide to cancel a project you’ve already started. Maybe they’ve found that they need to dedicate time and money to something else and what you’re working on is no longer a priority.

To protect yourself from losing out on what you’ve worked on, especially if you agreed upon a flat fee for the project, you need to include a kill fee, or ask for a down payment.

This will protect you from walking away without a dime in your pocket for the time you’ve put in. A kill fee can be a percentage of the total fee, or be based on all the work you’ve done up to the point of cancellation.

It can be a daunting task to write up a contract. But keep in mind that it doesn’t have to be full of legal language. Keep it simple and straightforward. Make sure your client understands it completely before you both put your signatures on it.

If you have no clue where to start with a freelance contract, read our article "How a design contract can help you manage clients," check out AIGA’s (very detailed) Standard Form of Agreement for Design Services or adapt this free graphic design contract from Rocket Lawyer.

The missing guide to the freelance designer's life is here

Learn everything you need to know about making the leap to freelancing, from how to find clients to how to price your services.

Be prepared for scope creep

What starts out as an update to a single landing page turns into a few more tweaks on a couple other pages. Then it turns into a complete design overhaul — of the entire website.

If you're charging an hourly rate, this can be great — as long as it's not eating into time you've already committed to other clients. Otherwise, you'll be doing extra work, without extra pay.

Agreeing to do extra, unpaid work isn’t “nice”

We all want to be accommodating and keep our clients happy. But when we start agreeing to do things that aren’t covered in the contract, we’re just encouraging bad habits — like the client thinking that extra tasks are just par for the course. Part of our job as freelancers is ensuring they don’t think that.

A contract saves you from doing additional work without getting additional pay. If a client needs something more, like an email campaign or a revamp of their social media content, you can add a change request clause to your contract. For anything that falls outside of the contract, such a clause can ensure you’re paid for your hard work.

Create deadlines for deliverables — and payment

This is why having a timeline of deliverables matters. If you’ve agreed on a timeline and a set fee, you need to be ready if the timeline gets extended. Every timeline should include a bit of wiggle room, but as a freelancer, you have to protect your time carefully — especially when you’ve got other clients in line.

Along with the timeline for the project, there also needs to be a payment deadline, and instructions on how to submit payment. This helps decrease confusion and ensures that you’ll be get what you earned in time.

Schedule time for feedback and edits

The feedback cycle needs to have limits, even if just to preserve your sanity.

Many clients don’t realize the overall implications of changes to a design. What seems like a small edit, such as repositioning an image or changing a font, can easily cause an avalanche of changes.

This ties back to the importance of a timeline. Allocate periods of time for revisions and specify what types of changes you’ll work on. For example, if the client tries to sneak a rebrand into a site design project, you’ll be well within your rights to say no — as long as your contract is clear.

Plus, keep in mind that, as a project progresses, certain changes become more difficult. It might be easy to reorganize content early on, but when the entire sitemap changes just before QA stage — well, that’s a whole other story. That’s why your contract should make provisions for late changes that may affect the entire project. Charging extra for changes that go beyond the timeline will protect you from doing excessive edits for free and keep your client in check if they tend to be nitpicky.

And, of course, you need to figure out who all of this feedback will be filtered through. Identifying a single person who will communicate edits to you will streamline the process, and force stakeholders to get on the same page. Having multiple people giving you feedback can result in conflicting ideas and muddy the project’s objectives.

Stop the creep

It's easy for a project to grow beyond what you've planned and take on a life of its own, like a monster breaking free from a mad scientist's lab. To avoid having to curse the creation you've unwittingly created, you need to set boundaries with your client. Communication is the key to avoiding scope creep. When both you and your client have a mutual understanding of the work involved, the process will be easier.