Zines have always been a way for underrepresented, excluded, or fringe ideas to be voiced and heard.

Unlike the usual distribution routes for ideas put on paper — traditional magazines, literary journals, art galleries or curated digital platforms — the zine’s simple format of printed art and writing in a self-published booklet allows anyone to distribute their work without much cost. All you need is something to share and a willingness to share it in order to create a direct line between you and a reader.

Though many zines today are distributed digitally, the origin of these “mini magazines” is in the messy, physical world of glue sticks, scissors, and paper scrap collages, resulting in intentionally nonstandard layouts that would give grid-lord Josef Müller-Brockmann a serious headache.

Zines are a tool for connection among fringe communities, in part due to the non-standard design but also because they are a unique outlet for concepts considered too left-field or inappropriate for public consumption. And just like its subversive sister, graffiti, zines have influenced generations of designers, artists, and creators — not just print, but in web design, too.

Today, as DIY coalition-building has been experiencing a renaissance, and resistance against the status quo is urgently overdue in the design field, zines might be the perfect playground for designers looking to join a fresh dialogue outside the boundaries of their backgrounds.

In fact, there’s already an exciting amount of zines produced from the drawing desks of artists quarantined at home, as well as DIY art spaces popping up to create community. So, in the true spirit of zinemaking’s DIY origins, I’m excited to share how you can not only draw from their influence in your own work, but also try it yourself — whether you’re picking up a pen and a pair of scissors or getting inspired by this alternative school’s long and many-faceted design lineage.

Who made the first zine?

The term “zine” as most know it is a 20th century invention. People familiar with zines tend to picture hastily-Xeroxed punk rants from the 90s containing content such as instructions for how to slash the tires on a police car while doing a cartwheel. (Yes, that is something you can actually read in a real zine.)

However, if you want to be pedantic (and I don’t, really), its roots technically go all the way back to the birth of publishing through the invention of paper and the first printing press. For instance, if you categorize political pamphlets under the phylum of zines, you could call Martin Luther’s Ninety-five Theses one of the earliest zines, or Thomas Paine’s Common Sense a zine. I’m choosing not to, but you could, since both men were using DIY publishing to speak out against corrupt establishments with their own “punk” counter-narratives.

Likewise, BLAST, an early art journal published in 1914, was not called a “zine” but got rather close, with its writers intending for the publication to be an avenue for “ vivid and violent ideas that could reach the Public in no other way.” Sounds pretty zine-y to me.

Last but certainly not least in the early Pantheon is FIRE!! (With two exclamation marks.) In 1926, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Wallace Thurman, Aaron Douglas, Richard Bruce Nugent, Gwendolyn Bennett, and John P. Davis created this invaluable editorial piece of history, capturing these Black artists’ uncensored perspectives during the height of the Harlem Renaissance when it’s likely that no other publisher would have done so. In a tragic irony, their headquarters were burned down, ending the project after just one issue — but they opened the door for the playwrights, novelists, and other creators who followed them.

I think the creators of FIRE!! are the first true zinesters — they wrote not just as an act of self-expression and defiance, but illuminated new possibilities for previously silenced and excluded artists, too.

The evolution of the zine

The evolution of the zine as a medium can be traced through the progression of the printing technology available to artists at the time. Mimeographs or low-cost proto-copiers were a descendent of the typesetting done on original printing presses. They first appeared in the 1870s and eventually helped budding science fiction “fanzines” (where “zine” comes from) lift off in the 1930s-1950s.

To make a fanzine in the 1940s, first, you’d need to be so passionate about whatever you were reading that you would be willing to hand-write original fan content, purchase a mimeograph, and have a plan to distribute them via mail, clubs, or conventions.

You’d then need to then type out your stencil on a sheet of fibrous material using a typewriter. If you were adding illustrations, you’d also need a hand stylus to etch the drawing onto the stencil. If you made a mistake, you’d need to use a special correction liquid to retype over your error. Last, you’d need to roll the stencil over paper in the mimeograph — finally creating your zine page.

Fanfiction over the decades has covered various styles and topics. Early fanzine readers were highly motivated subscribers, leading to a short-lived cottage industry of writers, distributors, and conventions.

That motivation proved to be extra-powerful when Star Trek was canceled after just two seasons in 1969. Outraged fans coordinated letter-writing campaigns, mainly through zines, which ultimately saved the show. When the show returned to air, Star Trek creator Gene Rodenberry actually encouraged show writers to reference fanzines when working on episodes, creating a dialogue between creators, actors, and fans that we can see mirrored on fan Twitter threads and in Patreon-exclusive content today.

When copiers became widely accessible through copy shops in the 1960s and 70s, zines underwent another renaissance, giving voice to countercultural movements in the US and beyond at the time.

In this iteration of the form, it became easier to quickly make hundreds of copies of hasty scribbles and collage layouts pieced together from other printed material. This mirrors how print layout was done at the time in mainstream media, with copy editors and graphic designers literally laying out designs on paper and gluing words into place. And it exploded from there.

In true zine fashion, punk and riot grrrl music scenes — especially in the Pacific Northwest — took this mainstream design technique and put a DIY spin on it. Members of the original riot grrrl bands Bikini Kill and Bratmobile made some of the first riot grrrl zines in the early 1990s, covering a wide range of feminist topics. Concurrently, they used similar design techniques in their album art, echoed in many more zine-style homages over the next three decades.

When we talk about such a print-driven medium arriving at the doorstep of the 2000s, it’s easy to jump to conclusions about how the dawn of the Internet age (summarized beautifully in this Webflow site) heralded a definite lull in print zine production. However, I’d venture that DIY websites like MySpace and Geocities, along with email newsletters, may have not only replaced quite a few zines, but made the information previously hand-printed and distributed in small circles much more accessible as well.

Today, as the design trends of the 90s have come back in fashion — zines are also having a moment.

Want to learn more about zine history?

- Listen to this episode of fan culture podcast “Author’s Note: Don’t Like, Don’t Listen” for a deeper dive into the relationship between sci-fi fanzines and the Star Trek subculture in the mid-20th century

- Check out A Brief History of Zines from the University of North Carolina’s Rare Books Blog if you skimmed this section and wanted a faster summary

- Read Punk Press: Rebel Rock in the Underground Press for a wild tour of the punk movement and its many artistic stylings

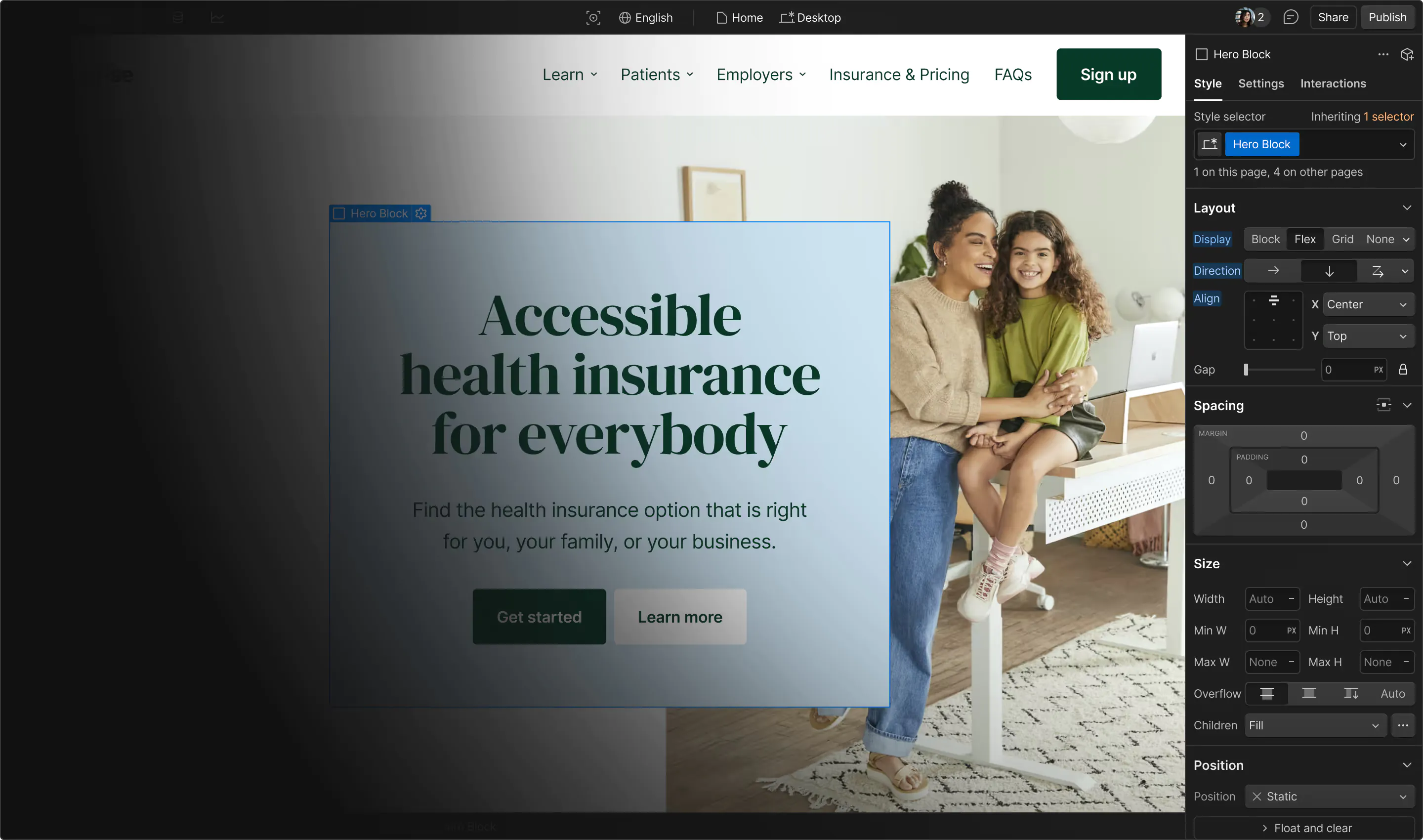

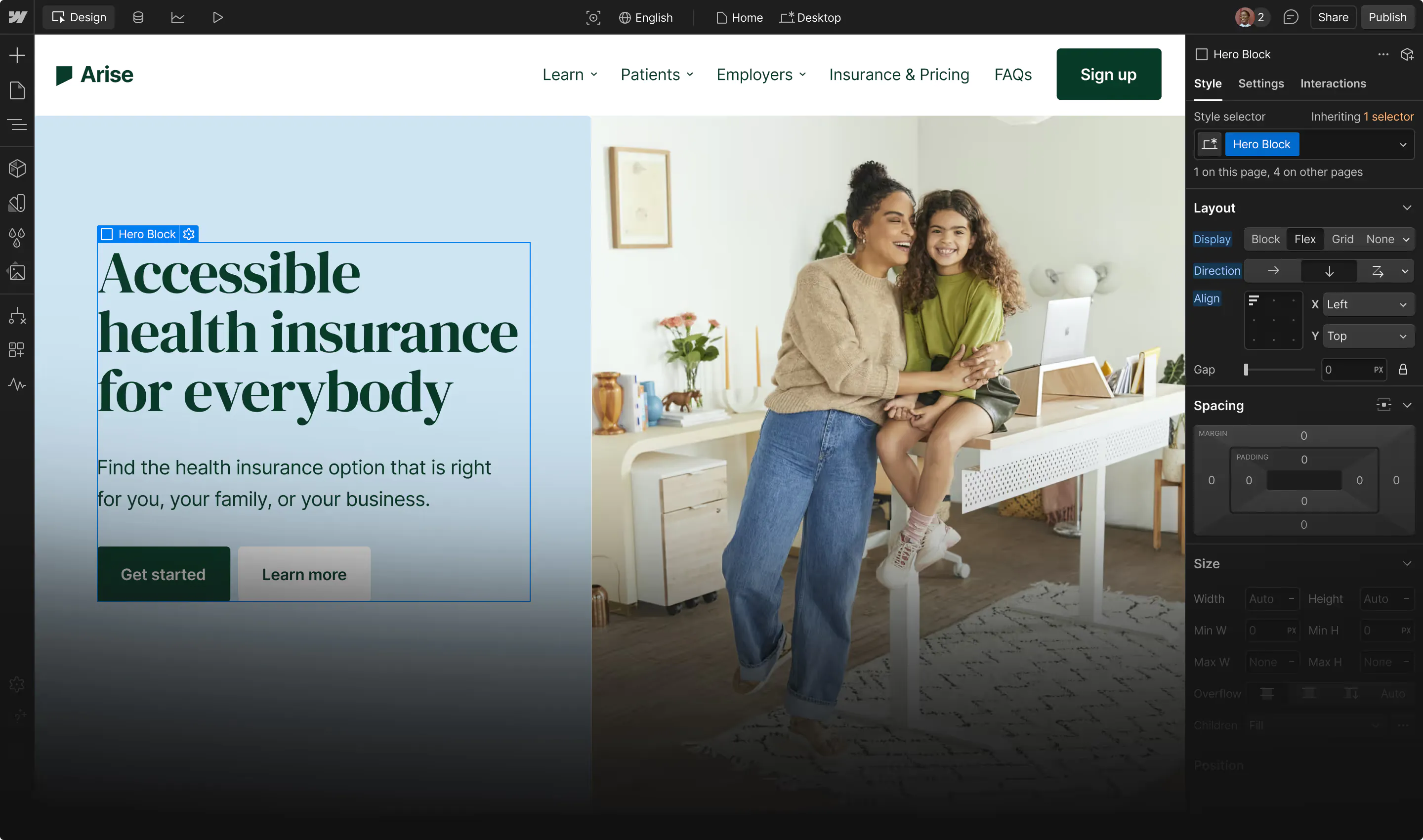

Build websites that get results.

Build visually, publish instantly, and scale safely and quickly — without writing a line of code. All with Webflow's website experience platform.

Zines and web design

The impact of print zines in web design today is widespread. For one, collage illustration is everywhere. After years of blah minimalism and corporate Memphis, we’re craving something tactile and real, drawing from physical-world design — especially when it veers into garishness or DIY.

Why on earth are we suddenly attracted to the imperfect? Personally, I think our eyes are tired of scrubbed-clean visuals and are now drawn to anything off-kilter, “ugly” or even (I’m whispering this quietly so my design professor from 11 years ago can’t hear me) intentionally poorly-aligned.

In a truly delightful honors thesis, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga scholar Lilith Jackson posits that designers can (and should) learn a lot from reading zines and emulating their DIY ethos:

“These designed artifacts live outside of the traditional collection of objects that are taught and retaught in graphic design history, which is not only a missed opportunity for beginning designers to learn about these countercultural histories, but also limits our understanding of what design practice can be. Zines offer graphic designers, and all makers, an opportunity to develop accessible content outside of the confines of commercial recognition.”

Some designers are taking note, even if only subconsciously or secondhand. Just take a look at this year’s web design trends to see zine-like inspiration everywhere. I’d take the liberty of calling the playfulness, informality, and creativity of microsites reminiscent of a zine. The revitalization of type-first, imagery-second web design we’re seeing everywhere this year clearly borrows from zines and print journalism, too.

One project I came across on Webflow Showcase directly references zines with its name, ZirkZine. The digital zine designed on Webflow by Sam Flick and run by Kenzie Zirkelbach has cheerful, fresh design that makes a lot of delightful references to print layout while staying current.

Echoing Lilith Jackson’s premise, Julia Lipscomb suggests in Communication Arts that picking up the analog resources and skills that are typically used to make zines — such as cutting and pasting, collaging, using newsprint, hand-writing, and hand-binding — can introduce more freedom into your approach:

“[...]Independently produced periodicals represent chaos, a diversion from more structured design projects and design “rules” that can cause a major obstruction in workflow. The nature of the zine enables the designer to see the zine’s design in print during the creative process instead of at the end and to create without an editor’s or a director’s approval — a process that is very freeing to the designer.”

Gaining that freedom is easier than you might think. Keep reading for a how-to guide on making your own zines.

How to find and read zines

Your first step to making a zine is to find and read some zines. The more variety in topics and formats, the better. I recommend gathering reference points the old-fashioned way (if that’s safe and accessible to you) by hunting down zines in your local community bookstores, college libraries, and counter-cultural spaces like co-op cafes. You may also have regular zine fests or fairs in your area you can check out (you may need to search online with some creative Googling), or even be lucky enough to live near a real-world zine distro like Wasted Ink.

Zine distros can be found online — check out Neither-Nor and Zine-o-Matic. My favorite low-cost zine publishers are PMPress and Last Word Press, but you can read many zines for free through online zine libraries like Sherwood Forest or the Queer Zine Archive Project. If all these links overwhelm you, just get started by following @nicezines for a curated lineup. However you find them, go explore and find some inspiration.

How to make your own zine

I got into making zines last fall (here’s one I made, and another) by stumbling across tutorials from TikTok zinester brattyxbre. The format felt like a great medium for voicing my feelings about political issues affecting me and people I care about. This form of expression has untethered a lot of crusty beliefs I held about myself as a designer — like thinking I’m not a designer at all — and opened up a whole new world of creativity and connection in my life. And if the #zinetok tag’s more than 8 million views are any indicator, I’m not the only person joining in on this resurgence.

I recommend starting with a simple 8-page mini zine like I did, which you can make from a single sheet of 8.5 inch by 11 inch paper. You just need a digital or physical tool for design like Illustrator or a pencil, scissors, and access to a printer with scanning/copying capabilities.

You have two basic design options from there:

- Design it right away with markers, photos, trash, scrap fabric, takeout menus – whatever you want!

- Use the digital design tool of your choice or the Electronic Zine Maker to lay out your pages, which will need to be 4.25” tall and 2.75” wide. Make sure to reference a pre-folded and numbered physical zine when you lay out your pages, since some of your pages will appear out of order and upside down in the digital copy.

Here are some of my tips and tricks for the process:

- Don’t make a zine with below 6pt font or it will be hard to read and be inaccessible for those with vision impairments. 8pt or more is best.

- Include at least a ¼ inch margin to allow for printing error so your art doesn’t get cut off.

- Avoid dark backgrounds, which will eat up printer ink and are more likely to smear or bleed when folding.

- I also recommend using a bone folder to make sharper folds that help the zine lay flat and to save your fingers and nails. You can typically pick up a plastic version of this centuries-old bookbinding tool at your local craft supply store for less than $5.

When you finish your zine (physical or digital), please take a picture and tag @webflow so we can celebrate your awesome creativity! Then, give a copy to a friend, drop it off at your local bookstore, or share the link on social media. Who knows whose hands it could end up in — or which design movement you might be starting next.