Imagine making art to cope with the absurdity of the world around you.

I don’t know about you, but as a marketer-by-trade trying to remember to take my meds every day during late-stage capitalism and rapid environmental collapse — any artistic movement born out of years of turmoil is worth a second look to me in this exact moment.

So I want to tell you about Dadaism.

Who were the Dadaists? What did they believe about the world? And maybe most importantly, how can creators today draw inspiration from their goofy perspective on rapid societal change and crusty institutions in desperate need of mockery and change?

Dada’s place in history

Dada is worth researching for yourself (trust me). The sum of all Western art history from the past thousand years is still a shockingly limited study of the human creative endeavor. Plus, I think the version presented in history books over-tidies up art history to skim over movements like Dada in favor of Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism — when really, these movements all overlap, inform, correct, and argue with each other.

Out of all of those glorious movements — which were still only representative of, say, about 50 French dudes’ artistic points of view during a brief span of a few decades, and were far from all-encompassing of all art movements in the world — I do have a soft spot for Dadaism in the same way I have a soft spot for Lil Nas X. Dada asks: “What if this was all funny tho?”

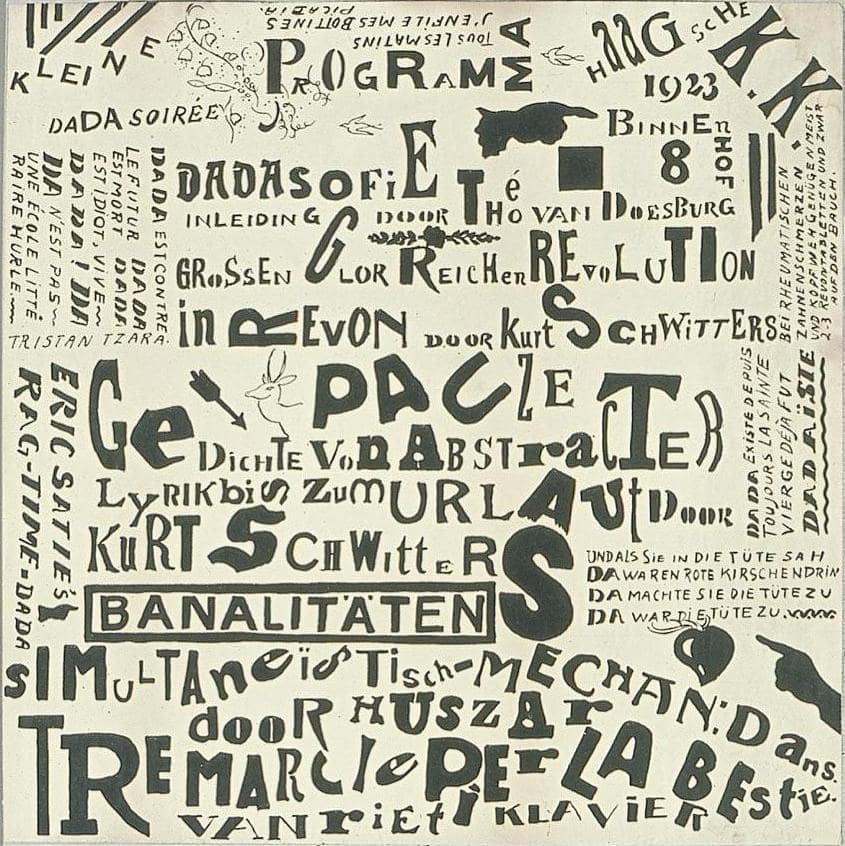

If the word “dada” sounds childlike, you’ve read it exactly as the movement’s creators intended. This European artistic movement of the 1910s-20s was brilliantly pre-postmodernist and aggressively childish. Confronted with World War I’s gruesome violence and existentialist dread, Dadaists chose absurdity over despair, like their Fauvist fathers before them. (Fauvism comes from the French word for beast, but that’s another story).

The ‘return to order’ and response

One of Dada’s dads is worth mentioning: Artists of the Rebel Art Centre in London. In 1914, they put forth a manifesto called BLAST for the avant-garde style known as vorticism, essentially a form of British futurism. The publication was meant to be an avenue for “vivid and violent ideas that could reach the Public in no other way.”

Dadaists wrote many manifestos of their own, but the one you need to check out is Tristan Tzara’s, published in 1918. Tzara left a prophetic mark on Dadaism (and in my opinion, zine culture) when he famously pulled words out of a hat to create a collage poem at a surrealist rally, now called the literary “cut-up method,” which is as close as we can get to a formal artistic term for refrigerator magnet poems.

Unfortunately, its production was cut short by World War I, and the art movement it represented was replaced by a postwar swing back into representative art, which was simultaneously being forcefully pushed back by Dada — a truly wild decade for art in Europe. So many of these movements were ultimately stifled again by a postwar return to order (yes, it’s as menacing as it sounds!) where people literally shell-shocked by grief and the pointlessness of war focused on creating representational art that didn’t challenge any norms.

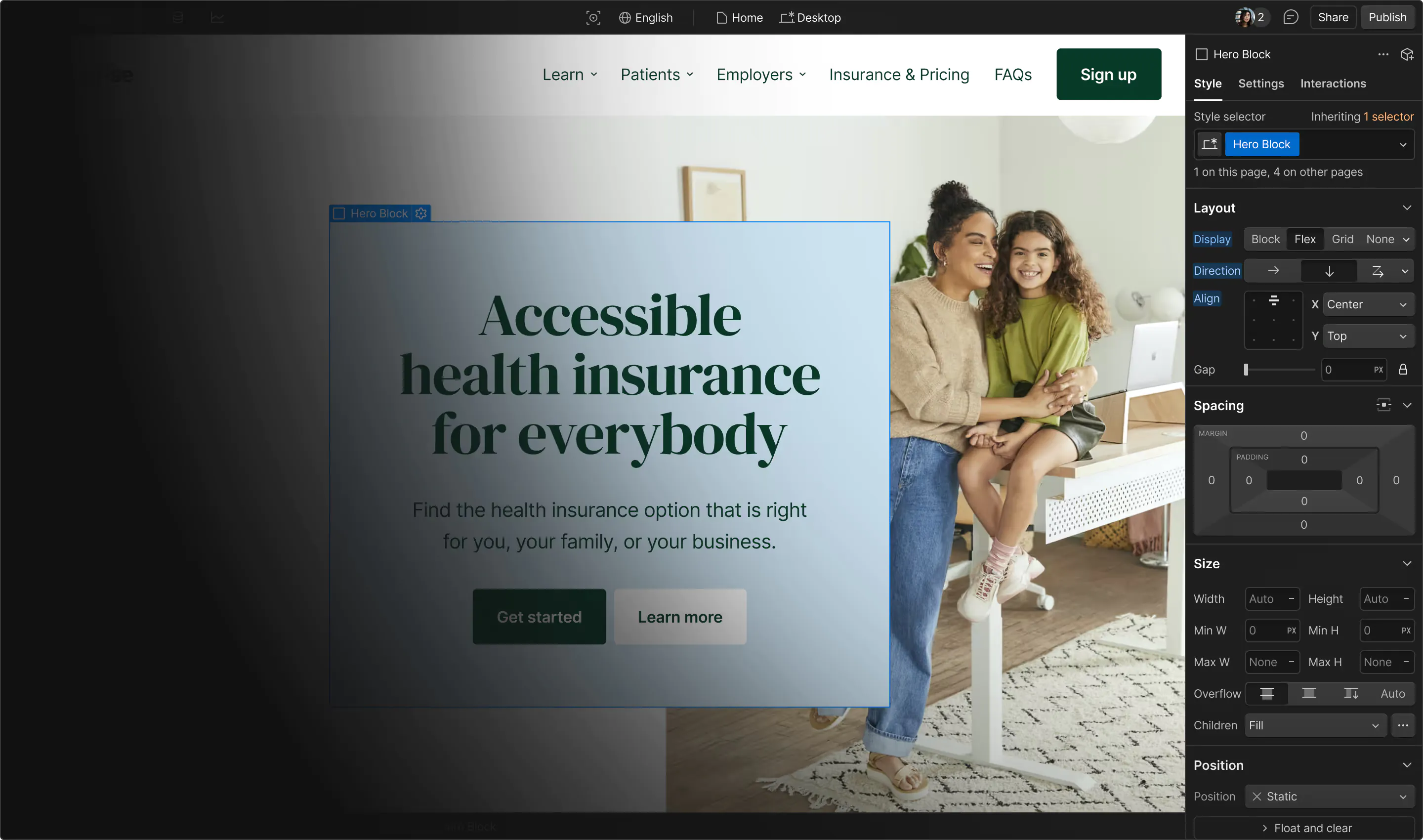

Get started for free

Create custom, scalable websites — without writing code. Start building in Webflow.

Dada stubbornly kept going, and I appreciate that. It’s the art world equivalent of playing a kazoo in the back of a very somber symphony — some people would consider it disrespectful, others would think it’s funny — either way, it would definitely call attention to the absurdity of the somberness itself.

Historically, there has been a rich Western tradition of building and then critiquing or destroying beloved cultural institutions. In my view, this happens because the West notoriously builds bad cultural institutions that are worth critiquing or destroying. It’s the critique or destruction that really carries weight, or in the words of communications theorist Marshall McLuhan, “the medium is the message.”

Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 piece “Fountain” is a great example — a urinal he signed with a fake name, would not have caused so much controversy were it not officially submitted to (and rejected by) the Society of Independent Artists in New York.

And perhaps Max Ernst would not have been motivated to provide showgoers with their own hatchet with which to destroy his sculpture in his 1920 unsanctioned exhibition Dada-Vorfrühling if he hadn’t been barred from museum exhibition in the first place.

There’s something there worth noting for any artist banging down the door of an institution looking for validation or acceptance. Maybe just turn up in a pub courtyard with your friends instead?

A contemporary take

I’ll follow the age-old tradition of critiquing past art movements with my own critique of Dada itself. I think Dada opened up a lot of avenues for playfulness and poking fun at the seriousness of art. But I also don’t think the movement went far enough.

To be fair, that’s a critique I have anytime a group of white dudes is smoking pipes in a Parisian studio talking about capital-F Form with what is essentially just a new flavor of pretension than their predecessors.

So if we draw from Dada and inspect our world today, let’s take the critique further to mock not just artistic institutions, but also draw attention to the cruel irony and absurdity of other constricting societal institutions, like incarceration, suppression of labor rights, or waste in manufacturing. Again, not for the purposes of being preachy or overserious, merely to say something worth saying — and to punch up at something that ought to be mocked and destroyed.

To strip pretense can be a pretense itself, or a performance, sure — so it’s a note I take as a creative person today to be mindful of what better world I demand when I modify or destroy old ones. Am I being performative in my critique? (Is this article a performance of a critique? Duchamp or Tzara might think so.)

The reason I think you should love Dada is that I believe designers could stand to employ a little bit more chaos, humor, absurdity, and joy in their work, and not take it so seriously all the time.

We’re off to a decent start: After our own decade of disgustingly sleek minimalism and Very Serious Design Publication Discourse, we’re seeing a resurgence of what I refer to as 90s chaos design, zine culture, and maximalism in graphic and interior design.

It’s good, but it’s not enough. I need to see you folks submitting toilets as your master’s theses at SCAD and RISD. Or at least provide me with a complimentary hatchet to destroy your painting. It’s the least you could do.

Further ways to explore Dada:

- The Smithsonian’s A Brief History of Dada

- ‘Behold the Buffoon’: Dada, Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo and the Sublime - Tate Papers

- The Fig-Leaf 1922 by Francis Picabia